- Home

- Carol Windley

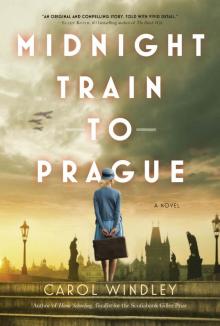

Midnight Train to Prague

Midnight Train to Prague Read online

Dedication

For Robert

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Part: One

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part: Two

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Part: Three

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Carol Windley

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part

One

In rivers, the water that you touch

is the last of what has passed and the first

of that which is to come; so with present time.

—LEONARDO DA VINCI

Chapter One

One day, she would return to her villa in the Palermo district of Buenos Aires, her mother said, speaking as much to a photograph on the wall in their Charlottenburg apartment as to Natalia. The photograph was printed on albumen paper. It was fragile, irreplaceable, and to her mother an object of veneration. Sometimes Natalia heard her speaking to it in Spanish, as if it had ears. The villa in the photograph had curved iron balconies, tall windows, and was set in a lush, subtropical garden with a marble fountain and peach trees espaliered against a stone wall. Although her mother hadn’t returned to Buenos Aires in something like twenty years, she had never sold the villa. She paid the taxes and the upkeep and the wages of a caretaker and his wife, who had the use of three rooms on the ground floor. On the globe in the living room, her mother traced a finger from the port of Hamburg across the Atlantic to the mouth of the Río de la Plata. In Buenos Aires, she said, she would walk to the Avenida de la Mayo and find a tram to Palermo, and she’d go in the door of her casa perdida, the lost house, and maybe she’d never leave again. What did Berlin hold for Beatriz Faber, a widow with no family to speak of? Not even her friends would notice she was gone. She gave the globe a push, setting it spinning crazily on its axis.

In this house, in Charlottenburg, it was a late summer’s evening; a fire crackled in the grate, and Hildegard, in the kitchen, was cooking dinner. The table was set with good china and crystal goblets. This is my home, Natalia thought, and I am happy here.

“Don’t look so sad, Liebchen,” her mother said, her silk dress rustling as she knelt beside Natalia. “I would never go anywhere without you. You know that, don’t you?”

* * *

In 1916, when she was six, Natalia began school at an Ursuline convent in Munich, where her mother said she’d be safer than in Berlin. But was anywhere safe, in a war? That summer, English and French planes dropped bombs on a circus tent in the town of Karlsruhe, killing seventy-one children as they innocently watched acrobats and lion tamers. In November, a French aviator bombed the Munich train station, damaging the stationhouse and a length of track, so that for weeks Natalia’s mother could not visit her at the convent. When the nuns told Natalia this, she was afraid it was a lie and that her mother had died in the war and was now a beautiful ghost in her stupid empty casa perdida. But her mother was well. She came to the convent and took Natalia home for Christmas. Natalia remembered lighting candles on the tree, going to Mass to pray for peace, and Hildegard cooking an enormous roast goose Natalia’s mother had procured on the black market.

At school she wore a dark blue tunic, a white blouse, itchy black stockings, black shoes, a double-breasted wool coat with brass buttons. There were eighty-seven pupils from the age of six to eighteen. That first year, Natalia was teased when she didn’t always understand the other girls’ Bavarian German, and someone stole her blue Teddy-Hermann bear from the pillow on her bed. Without him to comfort her, she couldn’t sleep at night or speak in class, which infuriated one of the nuns, who struck her across the knuckles with a ruler. A pair of gloves Hildegard had knitted for her disappeared, and outdoors, when playing in the snow, her hands turned blue with cold. A girl called Claudia lent her a pair of gloves lined with sheep’s wool. Natalia and Claudia became best friends, although the nuns decried their exclusivity and forbade them to sit together in class, where they had a lamentable tendency to giggle and whisper, Sister Johanna said, like chimpanzees.

Claudia’s mother was English; her father, a glassware merchant in Rothenburg, had gone to war with the Royal Bavarian Army. In October 1918 he fell in action in France. Claudia went home for the funeral and stayed with her mother and brother for two months, returning with a black mourning band on her coat sleeve and a cough that turned out to be the start of the Spanish influenza. The illness swept through the convent, afflicting the nuns and older girls first and working its way down to Natalia’s class. She was one of the last to become sick and was put to bed in the infirmary, where she heard a nursing sister say, This one is very ill. When the fever at last broke, she opened her eyes and saw her mother leaning over her with a glass of water. Just a sip, Natusya, she said, just a sip. Natusya was a pet name Natalia’s Papa, who had been half Russian, had given her.

Every morning her mother came to the convent from the Gasthaus where she’d rented a room. She carried trays of soup and dry toast from the kitchen up to the dormitories and the infirmary, changed bedsheets, administered alcohol baths to reduce fever, tenderly held girls racked by coughing. When the invalids began to recover, Natalia’s mother amused them by recounting the adventures of a girl whose name was Beatriz and who lived in Buenos Aires in a mansion with rose-colored walls and a southern aspect, near a park and a racetrack and a tennis court. This girl, Beatriz, had a governess, who often traveled with her by train to Montevideo or Rosario, where they had tea and went into shops, pretending to be locals. The governess, who came from Swabia, and was only a girl herself, liked to take long walks with Beatriz into the wilderness. They were not afraid of poisonous frogs or stinging insects or even of jaguars or of getting lost. The governess carried a pocket compass that indicated true north, even in the southern hemisphere, where the stars at night were not the stars of Europe. What happy times they had, those two, Natalia’s mother said, playing with a necklace of small blue beads around her throat. She sat up a little straighter in her chair and said that, sadly, an idyll cannot last. For some unspecified dereliction of her duties, Beatriz’s parents sent the governess home to Swabia, and those paradisiacal days came abruptly to an end.

The girls said: Is that all? Tell us more, Frau Faber.

They wanted to know: What happened to Beatriz? Where was Beatriz now?

In those days, her mother said, it was customary for Europeans living in Argentina to send their children home to be educated, and that was what Beatriz’s parents did. They sent her to her mother’s brother and his wife, in Berlin. Onkel Fritz and Tante Liesel, a childless couple in late middle age, adored Beatriz. They called her their Schatzi, their darling Mausbärchen, and showered her with gifts. They took her on vacations to the Côte d’Azur and Monte Carlo, to Vienna in winter, Paris or Budapest in spring. She learned to appreciate foreign travel, almost to crave it. But then, she told the girls, an exile was always searching for what had been lost.

Frau Faber had the face of an angel, the girls said to Natalia. The face of a Madonna. They asked Natalia: When is she coming to

see us again? Never, Natalia said firmly. Why should she share her mother with these girls? It was true, her mother had the face of an angel. People on the street saw her beauty; they smiled, they stared after her. But Natalia thought some of the convent girls were mean and didn’t deserve to have her mother wiping their noses and feeding them from a tray. Besides, it seemed wrong to her that her mother was pretending to be two people at once, the real Beatriz and the one who lived in that country on the globe of the earth in a villa that no matter how glorious it had once been, was nothing special, just an old image, susceptible to damage, erosion.

* * *

In November 1918, the war ended. Germany was defeated, the Hohenzollern dynasty vanished, and Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated and was granted asylum in the Netherlands. The Bavarian House of Wittelsbach and the Austrian House of Habsburg-Lorraine both collapsed—the latter like a house of cards, people said, and the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire simply ceased to exist. In the cities of Berlin, Hamburg, Weimar, and Munich, revolutionaries and paramilitaries battled in the streets. In Munich, the Bavarian prime minister, Kurt Eisner, was assassinated on a street not far from the convent. For a time, Munich became a Soviet Socialist Republic and took its orders from Moscow. The girls returning to the convent from visits home repeated what their parents had said. The British navy’s blockade of ships bringing food to German ports continued even months after the war ended. People were rioting in the streets over food shortages; children were dying of malnutrition. Then, in 1919, at Versailles, the Allied nations demanded Germany pay war reparations amounting to three billion gold marks a year. The Reichsbank was printing money like it was nothing, and it was nothing; three years after the war, the mark was worth less than zero. It was true, what their parents said, the girls all agreed: in Germany, the peace was worse than the war.

The nuns grew vegetables in the convent garden and kept chickens and gave every scrap, every crumb they could spare, to those in need. Natalia saw men begging on the street, lining up at church doors for a bowl of soup. Soldiers in filthy, torn uniforms, disfigured, sightless, missing limbs. Don’t stare, the nuns said, don’t pity them; they are brave men, they are heroes.

In Natalia’s history class, Sister Maria-Clare said God lived and moved in history; they were not alone in their suffering. As Germany’s future wives and mothers, they must have faith that life would improve. Natalia’s mother said something like this, in a very different way, when she spread documents out on the dining room table in Charlottenburg: land deeds, certificates of shares, stocks and bonds, passbooks to German bank accounts, statements from foreign banks. In 1914, weeks before war broke out, her mother’s friend Erich Saltzman, a senior official at the Reichsbank, arranged for a large part of her wealth to be sent out of the country, to Switzerland and then to “safe havens” in America and England. When the situation stabilized in Germany, as it would eventually, her assets would make the return journey, like a flock of migrating geese fattened up from a season in the sun.

It was not impossible to make money during a war, she told Natalia. Far from it. Property could be cheaply acquired; investments in armaments and coal and steel paid off handsomely. War was costly, she said, and as in most of life, the cost was borne by those who could least afford it. Not that she was any sort of Communist.

In 1924, on the advice of Erich Saltzman, Beatriz bought land in the new western Berlin suburb of Zehlendorf and hired an architect to design a villa for her. The house ended up being larger than she’d planned, too much for Hildegard to manage alone, and Beatriz found a Polish girl to help her. Trudy was young, skinny, wore a starched apron over ankle-length black skirts, spoke with a Polish accent, and adored Natalia’s mother. Hildegard and Trudy had their own rooms near the kitchen, looking out on the kitchen garden, where Trudy planted carrots, peas, and tomatoes. Hildegard brought home a black-and-white kitten. Natalia named him Benno and missed him desperately when she went back to school. But she liked school now that she was older, and Claudia was there, and she had more good friends as well. She enjoyed learning and worked hard, imagined doing something worthwhile with her life, and wondered, at times, whether she had a religious vocation and would enter a novitiate.

Then, on a dark March morning, snow falling outside the classroom windows, her mother arrived unannounced at the convent. In Sister Mary Ignace’s office, Natalia listened in disbelief as Beatriz said Natalia must pack her clothes; a taxi was waiting to take them to the train station. Sister Mary Ignace tried to convince Beatriz to give Natalia a chance to finish the term and write her final exams. A place at a university was assured; she could look forward to a rewarding career in one of the professions. Beatriz smiled. Her daughter, she said, would never need to work for a living. Anyway, she had plans; they were going to travel, do lots of interesting things. Surely Sister Mary Ignace would agree that seeing firsthand the world’s great cultural capitals equaled or surpassed whatever dry bit of information could be found in the pages of a book?

Beatriz, in a long crimson wool coat, like a prince of the church, was an incongruous, febrile splash of color in the principal’s austere office. She made Natalia’s eyes water. Later, when they were at home in Zehlendorf, her mother said they lived in modern times. Girls didn’t live sequestered behind stone walls anymore. And why even have a sixteen-year-old daughter if she couldn’t enjoy her company? They were going to have such fun. Did Natalia remember their vacation last summer?

Yes, she remembered, and it had been nice, the two of them together for a week at a resort on the North Sea. They walked great distances on the sand and went swimming when the water wasn’t too cold. In the afternoons they sat on the hotel veranda, watching seabirds skim the waves while fishing boats and freighters sailed past, far out at sea. By ten every night, Natalia retired to her room to read and was asleep before midnight, only to be awakened a short time later by Beatriz, throwing herself down on the bed beside her. She talked about the sore losers at cards, the handsome pianist who stared at her while he played Schubert, the young man with the eyes of a poet, who in fact was a poet and recited his sonnets to her from memory. The poet had spent some time in Buenos Aires and was thrilled to hear she’d been born there. She’d told him, and now she had to tell Natalia all over again, how her parents had emigrated to Argentina in 1879. They’d arrived in a new country with nothing and had built up a prosperous exporting business, working twelve-, sixteen-hour days, which hadn’t left much time for their daughter. Her father would say, Where is the little nuisance, and her mother would say she hadn’t seen her, even though Beatriz was right there, in front of her.

“You know, Natalia, that I never saw my mother and father again, after coming to Germany? Your grandparents Dorothea and Einhard März died in a cholera epidemic and are buried in the Recoleta cemetery in Palermo, which is like a city unto itself, a vast, strange, and rather ugly city of tombs. One day the residents of the Recoleta will arise, and they will all be reunited in Paradise. Isn’t that how it goes?”

“That is our hope, Mama. Were you and my father married, when your parents passed away?”

“I think so. Yes, I’m sure we were.”

“Tell me about my father.”

“I’m too sleepy, my darling.”

“Just one thing.”

“Your father was born in Königsberg.”

“Yes, I know. But I’d like to hear something new.”

“Oh, you are a little nuisance too.” Beatriz sighed. Alfred’s father and grandfather were cabinetmakers, she said. Their furniture was of such a high quality, it was coveted by Europe’s royal houses. A grand duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin commissioned a four-poster bed of such immensity a team of six horses was required to transport it to his castle. “One day, and this would have been around 1885, Alfred’s father cut his hand on a saw, or an adze, some implement, anyway, and within forty-eight hours he was dead of blood poisoning. The factory, the family home, and all the money went to Alfred’s uncle, while Alfred and his

mother were left with nothing, not even, ironically, a stick of furniture.”

But Alfred made a new life for himself. He became an importer of specialty goods from Eastern Europe: bolts of silk, furs, tinned caviar, Russian firearms, oranges from the Crimea, spices. He knew what people liked. He brought these commodities into Germany and sold them at a substantial profit. Truly he was a self-made man. She and Alfred were struck from the same mold; they didn’t let anyone get the better of them.

“What was my father like as a person?”

“As a person? Well, he skied in Thuringia in winter, and in summer he sailed on Grosser Wannsee. He smoked a pipe. In general, he found people disappointing and claimed to have no great expectation of anyone. He insisted on having his meals served on time. He was fond of his dog, Rufus. He liked the opera. Not the dog, I don’t mean. What kind of music the dog liked, I wouldn’t know. Alfred loved listening to Brahms, Chopin, Tchaikovsky. Sad music. Look on the bright side, I would say, and he’d say, Why must there be a bright side? He inherited his melancholia from his Russian family, not that I ever met any of them. They didn’t acknowledge your birth with a word of congratulations, let alone a gift. Natalia, I’m exhausted. I’m going to my room now.”

Natalia, unable to fall back asleep, listened to the sea rush-ing in along the shore and thought of the three photographs of Alfred Faber her mother kept in an embossed leather album in her desk. Three only. In one, taken in 1910, the year of Natalia’s birth, Alfred Faber stood in the Tiergarten, beside a perambulator, only the scalloped edge of a shawl visible, no sign of the infant within. In another, he stood outside the Adlon Hotel on Unter den Linden, a slight figure in a hat, gloves, a cane hooked over his arm. Then he was on the deck of a river steamer, at the ship’s rail, his face turned slightly away. She stared at these photographs, but what did she see? Not him, not really. She could not see the Russian in him, the music lover, the owner of a faithful dog, could not hear his “Natusya” or know if he loved her, if he’d had time before he died to feel anything for her. But always she gave the impassive face of Alfred a kiss. One kiss for each image.

Midnight Train to Prague

Midnight Train to Prague Home Schooling

Home Schooling